EDUCATION GUIDE

About the Education Guide

This guide was developed as a resource to support the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute’s exhibition, BYENVENI. The sections and suggested lesson activities below will explore the concepts of the exhibition to support a better understanding of Haiti's history and culture. The guide is broken up into sections, reflective of the exhibition’s galleries - Section I: Lespri, Introduction to Haitian Spirituality; Section II: Tè Nou, How to Define Home? Why Do We Leave Home; Section III: Lakou, Knowledge of the Community; Section IV: Poto Mitan, The Role of the Mother; Section V: Haitian Independence, What’s the Story Behind a Traditional Dish.

The historical context provided in this guide can be used while exploring the exhibition. The lesson activities are meant to be used in a peer group or classroom setting after exploring the exhibition.

This guide demonstrates how Haitian notions and concepts can have a universal significance. We invite you to utilize it as a resource for exploring the artworks’ main topics and establishing a connection with your own cultural background. Feel free to share all of your productions on social media by tagging us @cccadi

Table of Contents

-

Tips are offered on how best to utilize the guide for different student age groups.

-

BYENVENI Curatorial Statement

Understanding Lakay Se Lakay by Scholar-in-Residence: Queen Mother Dr. Dòwòti Désir

-

The Concept of Vodou

Lesson Activity I: Introduction to Haitian Spirituality

-

Haitian Migration Towards the World

Lesson Activity II: Defining/Leaving Home

-

The Lakou System

Lesson Activity III: Knowledge of Community

-

The Concept of Poto Mitan

Lesson Activity IV: Analyzing the Mother Figure

-

Haitian Independence and Soup Joumou

Lesson Activity V: What’s in a Traditional Dish?

-

The glossary includes key terms and definitions used throughout the guide and exhibition.

EDUCATOR TIPS

Each lesson is divided into two parts. First, participants will find a historical paragraph offering context and explanations about the concepts explored throughout each section of the exhibition, followed by a workshop activity to examine each theme. Learning objectives, instructions, and a note on materials needed are provided before each activity. In select activities, tips are available to make this guide more accessible to younger students, more adaptable for elementary/middle school students, and bonus sections are provided for high school and college students to encourage deeper analysis.

Intro to BYENVENI

Curatorial Statement

Yvena Despagne

My grandfather was the first from our family to migrate from Haiti to the United States in the late 1960’s, chasing the promise of “The American Dream” in hopes of establishing a stable home for his family and setting up an allurement of opportunities that would await his wife and four children. My mother, being the oldest of the four, was the last to arrive in the states, carrying me in her womb, unbeknownst to my grandparents and the unknown world that she would soon embark on as her new home, miles away from her beloved country. Although I grew up in Harlem, New York City, I was raised in the home as a Haitian child. Sheltered and cradled in the likelihood of holding fast to my Haitian culture. The laws were simple in my home and I was obedient to the three words embedded in my every being, Lekol, Leglize, Lakay! (school, church and home!). Traditions were annually the same, including having to drink Soup Joumou every 1st of January, but I never understood why. I never thought of myself to be a diaspora, nor did I think of the importance of carrying on the traditions of my Haitian heritage, until I came into my adulthood.

BYENVENI meaning welcome in Haitian Creole, is an exploration of the intricate tapestry woven by individuals existing within the Haitian Diaspora, navigating an interplay between their present environment and the enduring ties binding them to their ancestral homeland. This exhibition illuminates the multifaceted layers of identity, memory, and longing that characterize the Haitian Diasporic experience. Assembled within these walls are artworks that transcend geographical borders, capturing the essence of a shared narrative, serving as a poignant expression, encapsulating the yearning, and nostalgia inherent in being distanced from one's roots. The exhibited works serve as a testament to the profound emotional, cultural, and psychological bridges linking the Haitian Diaspora to their homeland. They reflect the ongoing negotiation between assimilation and preservation, belonging and detachment, as individuals navigate the duality of their identities—shaped by both the adopted land and the distant memories of their origins.

Haiti's cultural influence radiates far and wide, especially evident in its vibrant art, music, and religious rituals. This unique fusion of African, French, and indigenous Taíno influences has sculpted an unmistakable cultural identity. Moreover, it has remained at the forefront of global conversations, touching upon humanitarian aid, sustainable development, and worldwide solidarity. It is crucial that we acknowledge Haiti's profound significance on multiple fronts. The essence of Haiti's existence is pivotal, as it serves as a testament to the strength and determination of its people. It forms the solid foundation of a society's identity and longevity, encapsulating collective wisdom, revered traditions, and cherished values handed down through the ages. As I continue to grow a fondness for an understanding of who Haiti is and who I am as a Haitian, organically I continue to feel a closer connection to my homeland and in this sense, I feel welcomed.

Lakay se Lakay

BYENVENI is a multimedia exhibition that epitomizes the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute’s theme for 2024, Lakay se Lakay, which translates to Home is Home in Haitian Kreyòl. A year-long homage that celebrates the legacy of Haiti, Our Black Nation, Lakay se Lakay is a cultural odyssey through which we dedicate much of our programming.

Understanding Lakay se Lakay with CCCADI Scholar in Residence:

Queen Mother Dr. Dòwòti Désir

Her Majesty Queen Mother Dr. Dòwòti Désir is the Queen Mother of the African Diaspora, Bénin Republic. She lives in the United States of America and West Africa. As a human rights activist, interfaith leader, and writer, she has documented sites of consciousness throughout Africa, the Americas and Europe as they relate to the capture and kidnapping of Africans across the Atlantic. She joins us to initiate the start of CCCADI’s 2024 programmatic theme: Lakay se Lakay: Exploring the Legacy of Haiti. As our Scholar-in-Residence, HRM Queen Mother contextualizes why as a global African descendant community, anchoring ourselves in the revolutionary spirit of Haiti, Our Black Nation, is necessary for Diasporic solidarity and advancement.

We invite you to listen Her Royal Majesty Queen Mother Dr. Dòwòti Désir to immerse yourself in the concept of Lakay se Lakay.

SECTION I

Gallery A: Lespri

(The Spirit)

The Concept of Vodou

(Haitian Spiritual Tradition)

Vévé.jpg

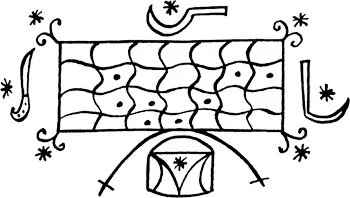

Vodou is an ancient wisdom system and spiritual tradition encompassing philosophy, medicine, justice, and religion. Its fundamental principle is that everything is spirit. Humans are spirits who inhabit the visible world (or all that is seen). The unseen world is populated by lwa (spirits), mistè (mysteries), envizib (the invisibles), zanj (angels), and the spirits of ancestors that recently transitioned into the ancestral realm (in Vodou, there is no concept of death; life is energy that has transformed or transitioned into another form). All these entities are believed to live in a mythic place called Ginen, a cosmic Africa. God (embodied in both masculine and feminine) is understood to be the creator and source of both the universe and the spirits inhabited within. Spirits are derived from God and help navigate humanity and the natural world. (Photo: Milokan Veve, a lwa in Haitian Vodou that represents a force of unity among the lwa and deities.)

The spiritual and religious aspects of Vodou practiced in Haiti include a syncretism of the West African Vodou religion by the descendants of the Dahomean, Kongo, Yoruba, and other ethnic groups and nations who had been enslaved and transported to colonial Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was known then), and partly Christianized by Roman Catholic missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries.

One of the core practices of Vodou is to sèvi lwa (serve the spirits/deities) — to offer prayers and perform various devotional rites directed at the divine and particular spirits in return for health, protection, and favor. Spirit possession plays an important role in this tradition, as it does in many other world religions. During religious rites, practitioners sometimes enter a trancelike state in which the devotee may eat and drink, perform stylized dances or special physical feats, and provide supernaturally inspired advice or medicinal cures to people. These are the ways a devotee might embody and exhibit the incarnate presence of the lwa in their physical body. Vodou rituals (e.g., prayer, song, dance, ceremonies, divination, and medicinal herbs) seek to restore balance and energy in relationships between people, and between people and the spirits of the unseen world.

Within Vodou is a powerful oral tradition practiced by extended families that inherit familial spirits, along with the necessary devotional practices, from their elders. Local hierarchies of priestesses or priests (manbo and oungan), “children of the spirits” (ounsi), and ritual drummers (ountògi) comprise more formal societies or congregations (sosyete). In these congregations, knowledge is passed on through a ritual of initiation (kanzo) in which the body becomes the site of spiritual transformation. There are some regional differences in ritual practice across Haiti, and branches (also known as nations) of the religion include Rada, Daome, Ibo, Nago, Dereal, Manding, Petwo, and Kongo. There is no centralized hierarchy, no single leader, and no official spokesperson, although various groups sometimes attempt to create such official structures. There are also secret societies, called Bizango or Sanpwèl, that perform a religio-juridical function.

In Vodou, the poto mitan, refers to a central pillar or column within the temple (or peristil) around which ceremonies, rituals, and gatherings take place. It holds significant, symbolic, and practical importance within Vodou practices as it represents the connection between the earthly realm and the spiritual realm. The pillar is seen as the axis mundi, the axis connects earth and Ginen, and is believed to provide stability, support, and a point of convergence for spiritual energies during ceremonies and rituals.

A calendar of ritual feasts, syncretized with the Roman Catholic calendar, provides a yearly rhythm of religious practice. Notable lwas are celebrated on saints’ days (for example, Ogou on St. James’s Day - July 25; Èzili Dantò on the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel - July 16; Danbala on St. Patrick’s Day - March 17; and Gede on All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day - November 1 and November 2). Many other familial feasts (for the sacred children, for the poor, for particular ancestors) as well as initiations and funerary rituals occur throughout the year.

Sources: “Nan Dòmi: An Initiate's Journey into Haitian Vodou” by Mimerose P. Beaubrun Manolia Charlotin, cultural educator, researcher, journalist

Lesson Activity I: Introduction to Haitian Spirituality

Learning Objectives: Participants will gain a better cultural understanding of African-rooted spiritualities and self-spirituality.

Estimated completion time: 15 minutes

Materials Needed: Drawing tools such as pencils, markers, crayons, etc., and a blank sheet of paper, recommended size: 8.5 x 11.

Instructions:

Participants will look at Metrès Riva Nyri Précil altar and think about its composition. What is it made of?

Each participant should look at the documents that introduce the main Lwa (gods) in Vodou and choose one they feel the most connected to.

Choose five (5) objects/elements that would compose their altar, embody their spirituality and connect them to one of the lwa's elements/theme/subject.

Compose, draw or write about their altar.

Resources: Metrès Riva Nyri Précil, Exhibition Artist

Notable Lwa in Haitian Vodou and Their Attributes

Reflection questions:

Why do people feel the need to materialize their spiritual beliefs through objects/installations such as an Altar?

Why did participants choose those specific objects to create their altar? What do they represent to them?

Bonus for High School and College students: To add a deeper layer to this workshop, participants must think of how Christianity and Vodou/animist religions interact in Latinx, Caribbean, African and African American societies. Think of different examples from various cultures to redefine religious beliefs, practices and customs as either cultic or cultural.

Vocabulary: Syncretism; the combining of different religions, cultures, or ideas.

Source: Cambridge Dictionnary

II. Gallery B: Tè nou

(Our land)

A Note on Migration

Migration from Haiti has been happening in waves since the Haitian Revolution and continued steadily through the Harlem Renaissance and World War I. However, migration en masse truly began during the dictatorial regime of Francois Duvalier and son, Jean-Claude. In those three decades, almost 1.5 million Haitians were displaced because of political terror and severe economic decline due largely in part to the country’s coffers being pillaged by the regime and devastating economic policies of the U.S. government towards Haiti.

The first major wave in the 1960s settled largely in New York City, making it the heart of the Haitian Diaspora community. And in those days, you could find a majority of Haitian immigrants living in Harlem and upper Manhattan. Within a decade, Haitians had also built large communities in Miami and Boston. (Note: Montreal, Canada had also become a major hub for the Haitian Diaspora and remains so today).

Sources:

HAITI: A Brief History of a Complex Nation | Institute of Haitian Studies.

Anténor Firmin challenged anthropology’s racist roots 150 years ago

Manolia Charlotin, cultural educator, researcher, and journalist

PÒTOPRENS: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince (exhibition book)

Lesson Activity II: How to Define Home? Why Do We Leave Home?

Learning Objectives: Participants will analyze different forms of artwork to define Home and apply a writing method using literary devices to compose a poem.

Estimated completion time: 30 minutes

Materials Needed: A device to listen to the song, and a digital or physical document to write a poem.

Instructions:

Participants will listen to the song “Ayiti Se” by Mikaben.

Notice the two literary devices used in the lyrics: Enumeration + Anaphora (see vocabulary for definition).

Look at Tania L. Balan-Gaubert’s artwork “Promise”.

Have a brief brainstorm about it with the other participants. (What are the main ideas presented in the piece?)

Read “Home” by Warsan Shire (not recommended for younger participants) and/or ‘Haiti’ (poem) by Joel Francois.

Write a poem describing what it would mean to leave your homeland, inspired by the poems “Home” and “Haiti”, using enumeration and anaphora literary devices.

(Optional) Send us the student poems!

How to use submit poems:

Go to this link: shor.by/homepoem

Fill out the form (Email address, Full name (optional), Upload your poem)

Submit the form

-

‘Ayiti Se’ (song) by Mikaben + Translation here

‘Home’ (poem) by Warsan Shire (not recommended for younger participants)

‘Haiti’ (poem) by Joel Francois

‘Promise’ (boat) by Tania L. Balan-Gaubert *exhibition artist* + description

Promise, a nautical bookshelf adorned in sequins, resembles the brightly painted public transportation vehicles popular in the Global South and known as “TapTap” in Haiti. The boat’s solo companion, a small citrus tree, sits atop satin pillows, black and covering the boat's length like a casket. Traversing the space between the physical plane and the spiritual realm, Promise is a statement about migration, diaspora, and the generational ripples caused by separation and isolation from one’s home/land. I am the tree my parents and their parents journeyed from Haiti to the United States to see blossom. I am the child seeking her mother/land, and I am the promise, an ever-unfolding potentiality that navigates a new world.

Vocabulary:

Enumeration: the action of mentioning a number of things one by one

Anaphora: the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses.

Elementary School Educator Tips: Remember to explain the literary devices, enumeration, and anaphora, to ensure student comprehension of the task.

Bonus for High School and College Students: Now that participants have brainstormed on why someone may leave their homeland, let’s think about what happens when settling in a new country, considering how the Black Diasporas interact with one another in the United States. What does it mean to be Black in the United States considering the differences between Caribbean (i.e Haitian), African, Black Latinx and African American cultures? Is there such a thing as a Black American identity? We invite participants to think of the relationships between People of Color within the United States and in their neighborhoods, particularly Black communities. To help with this question we recommend referencing the book, “The Making of African America: The Four Great Migrations” written by Ira Berlin.

III. Gallery C: Lakou

(A Communal living space)

The Lakou System

(A traditional system of communal living in Haiti)

The Haitian model of lakou is one of the most important aspects of Haitian society. This traditional system of communal living is a direct legacy of the Maroon societies that fought against the economic and social system of slavery plantations. As Mimerose P. Beaubrun wrote in “Nan Dòmi, An Initiate’s Journey into Haitian Vodou”:

“Lakou, a kind of vital space, a place of multidimensional life where several families or, rather, an extended family shares all aspects of life (spiritual, economic, cultural). In fact, the lakou has three functions: preservation, protection, and renewal.”

The word lakou refers to the open yard space shared by a cluster of homes; designates a cluster of families and extended families that organize around a central open space to live together and mutually provide for their needs. It is a multi-generational family and community system that guides land management, family and collective ownership, cooperative labor, and trade practices. This sort of micro-society system is common in rural communities of Haiti, allowing people to organize in such a way to be self-sufficient and independent.

Sources:

Sabine Malanblache, “

Mimerose P. Beaubrun, “Nan Dòmi, An Initiate’s Journey into Haitian Vodou”

The Lakou System: A Cultural, Ecological Analysis of Mothering in Rural Haiti

Manolia Charlotin, cultural educator, researcher, and journalist

Lesson Activity III: Knowledge of Community

Learning Objectives: This activity enables participants to examine the different pillars of their community by capturing their environmental landscape. It allows them to record the strengths and concerns of their community and the impact it has on their lives. Through this activity, participants will share the structure of their neighborhoods and experiences and have critical dialogues about their surroundings.

Estimated completion time: 25 minutes

Materials Needed: A blank piece of paper, recommended size 8.5 x 11 and drawing tools including a ruler.

Instructions:

Participants will look at the “Lakou map".

On a blank piece of paper, they will draw a map of their own neighborhood based on the Lakou map.

Identify the most important places for the community.

Place them on the map.

Think of how the community would be impacted if one of them didn’t exist anymore.

Participants should compare their maps to one another’s. (Is it the same? What are the differences? Do they have the same vision of their neighborhood/home? What do they value the most?)

Explore dialogues about how they could get more involved in empowering their community/home.

Bonus for High School and College students: Participants can think of what infrastructures are missing in the community and imagine a development plan. To go even further, they can include the aspect of gentrification in their reflection. How can a community preserve its neighborhood from gentrification and develop it at the same time? How might gentrification impact or have impacted their neighborhood or a neighborhood they are familiar with?

IV. Gallery C: Poto Mitan

(Central pillar)

The Concept of Poto Mitan

Fanm se poto mitan (Haitian women are the central pillar) is a common proverb in Haiti. It highlights the central role women play in Haitian society, similar to the central pillar of the lakou. Metaphorically, the poto mitan symbolizes the backbone or spine of the community, providing strength, unity, and guidance for the practitioners. In a lakou, for example, it plays a quintessential and central role as a physical structure and a representation of spiritual connection and community cohesion.

The central role women play not only in Haitian commerce, but also within Haitian families. In Haiti, 70% of rural households are headed by women, despite a history of embedded male dominance. Against the backdrop of ongoing poverty, socio-political crisis, and gender discrimination and oppression, Haitian women have been the stabilizing force to uphold unique African traditions of feminine power, womanhood, sisterhood and multiple mothering within a distinctive African space such as the lakou. Since the 19th century (1804), the lakou, referring to family members and the cluster of houses in which Haitian families reside, has been the principal family and extended family form.

Initially, the members of a lakou worked cooperatively and provided for each other through financial and other forms of support (LaRose 482). Moreover, the original lakou was based on the African reality that raising children was too great a responsibility for only one or two people to bear, and that it was healthier for children — and mothers — to have contact with a wide circle of people and share parenting responsibilities (Ambert 530). Therefore, within this location or bounded space, where children have multiple caregivers, Haitian mothers were able to carry out their traditional functions according to the healthy, successful parenting models of Haitian communities.

Sources:

Lesson Activity IV: Analyzing the Mother Figure

Learning Objectives: Participants will identify the role of mothers and make a collective representation of motherhood.

Estimated completion time: 25 minutes

Materials Needed: Photographs or drawings, digital or scanned (if submitting to communal mosaic).

Instructions:

Participants will look at the two artworks and compare them.

Think of how the artists represented their vision of motherhood.

Participants should imagine how they could represent their vision of motherhood (based on the artworks they see) in one word/picture/drawing.

Produce it in a way that it could fit on a square paper.

Assemble it with other participants’ production to create a mosaic of motherhood representations.

Optional: Upload their production on our collaborative mosaic and see every participants’ vision of motherhood.

https://mosaically.com/photomosaic/f39a3f23-940a-4eae-92ba-f947a845f654

V. Gallery C: Haitian Independence

Haitian Independence and Soup Joumou

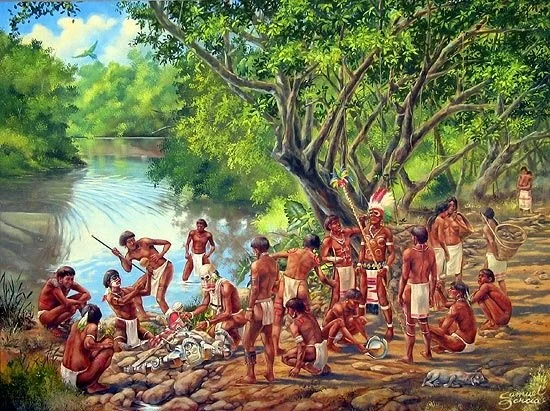

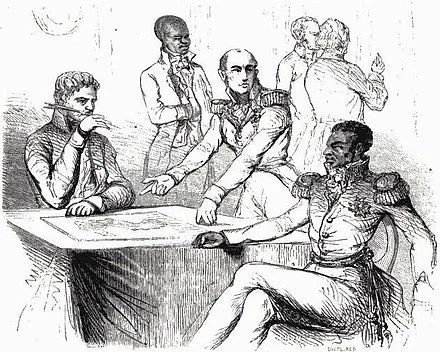

The Haitian Revolution is the largest and most successful revolt of enslaved people in the Western Hemisphere. The ceremony of Bwa Kayiman on August 14, 1791 served as the launch of the Haitian Revolution, which took place in the north of Haiti just outside of the second largest city, Cap-Haitien. This sacred gathering was the result of months of strategy and planning led by Cécile Fatiman, a Manbo (or Vodou priestess) and Dutty Boukman, a Jamaican maroon and Vodou priest.

The revolution was a complex 13-year military campaign, consisting of several rebellions going on simultaneously. Led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, who would become governor of the whole island until his capture by France. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of the fierce generals who served under L’Ouverture, would go on to lead the revolutionaries and defeat the French army at the Battle of Vertieres on November 18, 1803.

On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared the nation independent from colonial rule and enslavement, renaming it Haiti (Hayti - original spelling; Ayiti - Creole spelling) to honor the indigenous lineage. Haiti emerged as the first Black republic in the world, and the second nation, after the United States, to win its independence from a European power in the western hemisphere.

Soup Joumou (also referred to as freedom soup) is a traditional dish commonly eaten in the Haitian household every year on Independence Day, to signify the anniversary of freedom from colonial rule. This dish is made with squash (in Haiti they use Haitian pumpkin) puree and beef stock base, with a mixture of potatoes, pasta, cabbage, onion, leek, turnips, carrots, and celery. Prior to the revolution, enslaved Africans would prepare this dish for plantation owners and the upper class, who were the only ones allowed to enjoy the soup. Following the victory of Haitian Independence, Dessalines asked his wife, Marie Claure Heureuse Felicite Bonheur Dessalines, to prepare and serve this dish to the freed Haitian people. This was to send a message to the former colonizers. Now, Haitians in Haiti and throughout the diaspora enjoy this soup to honor the memory and spirit of their ancestors who fought for independence.

Source:

https://abcnews.go.com/US/colonial-era-debt-helped-shape-haitis-poverty-political/story?id=78851735

Manolia Charlotin, cultural educator, researcher, and journalist

Lesson Activity V: What’s the story behind a traditional dish?

Learning Objectives: Participants will learn the history and components of traditional dishes and become more aware of the historical events that inspired or helped create them. Once they understand its historical and cultural background, they will write their own recipe which can include mixing, cooking along with poetic and historical elements.

Estimated completion time:

20 minutes + research time

Materials Needed: Writing materials.

Instructions:

Participants will think of a traditional dish that links them to their cultural background.

Research the foods' history by searching online and talking to friends, family and peers. (Where do the ingredients come from? Why and when was it invented?)

Write its recipe using poetic images relating it to its history.

Bonus for High School and College students: Participants can create a survey addressed to their circle/community about their traditional meal. They can ask for instance: - Do the members of their community currently eat the meal? Do they prepare it? Do they know when it was invented? Why is it a traditional meal? Based on the responses they can identify the aspects of the meal’s history that need to be taught.

Educator’s note: Participants can prepare a poster explaining the story and the recipe of the meal and display it in schools or other community spaces.

Glossary

Acknowledgements:

BYENVINI Exhibition

Curator: Yvena Despagne

Artists: Nic[o] Brierre Aziz

Steven Baboun

Daveed Baptiste

Tasha Dougé

Laurena Finéus

Tania L. Gaubert

Madjeen Isaac

Fabiola Jean-Louis

Metrès Riva Nyri Précil

Natacha Thys

Oyasound Project

Education Guide: Paloma Dubois, Education Intern

Manolia Charlotin, Lakay se Lakay Consulting Producer

Alyssa Friday, Education Intern

BYENVENI is made possible by the generous support of the New York State Council on the Arts, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York City Council Speaker Diana Ayala, New York City Councilmember Crystal Hudson, New York City Councilmember Sandy Nurse, New York City Councilmember Althea Stevens, The Howard Gilman Foundation, The Pinkerton Foundation, Grantmakers for Girls of Color, and the Warner Music Group/Blavatnik Family Foundation Social Justice Fund.

LAKAY SE LAKAY

BYENVENI is a multimedia exhibition that epitomizes the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute’s theme for 2024, Lakay se Lakay, which translates to Home is Home in Haitian Kreyòl. A year-long homage that celebrates the legacy of Haiti, Our Black Nation, Lakay se Lakay is a cultural odyssey through which we dedicate much of our programming.

Learn more about all of the Lakay se Lakay themed programs: cccadi.org/lakay